|

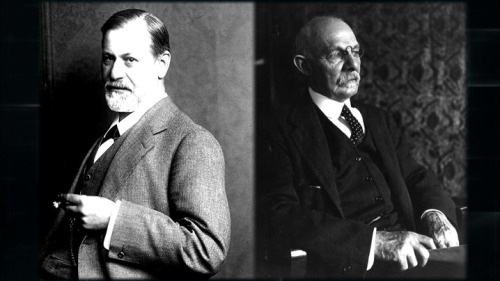

| Sigmund Freud and William Halsted

By Howard Markel, New York, Vintage Books, 2012, p. 314

I'm interested in the history of addiction and specifically how the scientific understanding of the causes, cures of addiction have changed over time. Markel, a professor of the history of medicine at the University of Michigan and a medical doctor, has written a wonderful history of drug addiction among two leading doctors in the 1880s. With careful and engaging scholarship, Markel examines how cocaine addiction influenced the work and life of Sigmund Freud and William Halsted. Freud, of course, is the father of psychoanalysis and William Halsted was, arguably, the most innovative surgeon of his time and the first Professor of Surgery at Johns Hopkins University. In brief, cocaine was heralded as a wonder drug that would treat depression, indigestion, addiction, neurasthenia, and assorted aches and pains. It also functioned as a powerful anesthesia. In the 19th century, doctors prescribed opium, morphine, and laudanum (opium in 50% alcohol) to control pain, and the concept of "illegal drugs" did not exist. Both Freud and Halsted experimented with cocaine on themselves and became addicted. The addictive properties of pain medicine were not understood. Drug addiction at this time was defined in moralistic terms: cocaine was not addictive in itself, and addiction was a vice. The person who suffered from a substance abuse problem possessed "an addictive personality." Addiction was an evil habit to be overcome, and only those favored or forgiven by God had a chance of success. Freud compulsively used cocaine from 1884 to 1896. Markel denies an easy causal relationship between Freud's cocaine use and his theories of a universal mind. He notes, however, "In some sense, Sigmund's cocaine abuse represents a pharmacologically induced, perverse object lesson about the power of uninhibited expression for gaining access to deeper, unconscious levels of psychological meaning." Markel is a careful historian and clearly lays out what his primary source documents will and will not tell him, and, therefore, he portrays a more nuanced portrait of William Halsted than Freud. Halstead's story is the core of this text. The historical record of Halsted's struggles with addiction is complex. Colleagues and students wrote secret memoirs that detailed their observations of his behavior. Halsted's affliction was present to those trained to recognize symptoms, yet the politics of accusing such a respected surgeon-scholar of drug abuse were prohibitively difficult. Halsted's reputation would be destroyed, Johns Hopkins standing would be affected, and the accuser himself risked his own standing in the medical community. Halsted's dependence on cocaine was treated with morphine, and this caused additional problems that lasted his entire life. He took morphine daily and struggled with periodical lapses of cocaine abuse. Once at Johns Hopkins, Halsted was enormously successful: he developed new surgical procedures, created a surgical residency program, and authored innovative papers. He elaborated an extremely time-consuming, exquisite manner of operating called the "School of Safety." Its amazing that Halsted could rise above his drug addictions to achieve real greatness. Halsted's demons, however, took their toll on him both personally and professionally. He was a deeply unpleasant man: he had a remote demeanor, was frequently rude, and acted from a position of privilege secure in the knowledge of his own genius. Markel's description of Halsted's determination to participate in medicine despite his afflictions moved me to tears. Summarizing his thesis in the book's conclusion, he writes, "In defiance of the malady that nearly destroyed them, or perhaps because of their struggle to overcome it, neither man ever lost his zeal for delivering his healing gifts to the world." Halsted's intellectual prowess and unabashed ego (Markel claims that he had "a controlling personality of epic proportions" ) joined with an empathy for the sufferings of others. |

A diary devoted to reading the 100 novels cited in Jane Smiley's 13 Ways of Looking at the Novel

Friday, February 15, 2013

An Anatomy of Addiction: Sigmund Freud, William Halsted, and the Miracle Drug Cocaine

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment