|

| The Pink Sugar on display inside the Hofburg Palace

By Frederic Morton, DaCapo Press, 2001

This is a companion volume to Morton's A Nervous Splendor: Vienna 1888/1889 and rounds out his history of the Austro-Hungarian empire. His histories are compulsively readable and very enjoyable. Sweeping, synthetic overviews like this are a good first step in learning about the past.

|

A diary devoted to reading the 100 novels cited in Jane Smiley's 13 Ways of Looking at the Novel

Monday, December 9, 2013

Thunder at Twilight: Vienna 1913/1914

Gulliver's Travels

|

| In the country of the Houyhnhnms

By Jonathan Swift, WW Norton and Co., 2002

I haven't read this story in over twenty-five years. A sharp satire and surprisingly physical. There is, in terms that I connect with my new puppy, wee and poo everywhere.

|

Nightmare Abby, Crotchet Castle

|

| Thomas Love Peacock in later life

By Thomas Love Peacock, New York, Penguin Books, 1986

I love satire and I love the Romantic British poets, so how could I fail to revel in these gems by Thomas Love Peacock? He was good friends with Shelley and these novels are send-ups of Regency intellectual trends and cultural fads. So far, so good, but I felt excluded. I dutifully read all the textual notes that explain the various debates to the reader, yet I only felt a distant type of bemusement. Not only is there Latin but plenty of Greek too! This is a story about men for men. I was reminded of the plays by Sheridan in the humor: characters sport names that indicate their personality or opinions (e.g., the Reverend Mr. Larynx, the Honourable Mr. Listless). I'll try rereading this in the future. |

The Expedition of Humphry Clinker

|

| Thomas Rowlandson, The Exhibition Staircase, ca. 1811

By Tobias Smollett, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2009

My favorite 18th century novel. Its a travelogue and the funniest book in the English language.

|

Robinson Crusoe

|

| Francis Cotes, Edward Knowles, c. 1740

By Daniel Defoe, New York, The Modern Library, 2001

I really can't believe this is the same author that wrote Roxana and Moll Flanders. Defoe's tone is sympathetic and humane here. When Robinson Crusoe is marooned on the island, he behaves like an industrious, pragmatic member of the middle class and slowly recreates his world. He builds shelter, hunts for food, domesticates animals, builds a ship, etc. A very interesting comment on gender, class, empire and race. What startled me is how this is a Protestant tale par execellence. |

The Female Quixote

|

| Allan Ramsay, Jean Abercomby, Mrs. Morison of Haddo, c.1767

Charlotte Lennox, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1997

Arabella reads French novels and decides to act as a heroine in the drama of her own life. She lives her life according to the manners and values of romances, and this makes her unfit for 18th century society. A charming, funny book. Jane Austen read this novel twice. |

Thursday, October 31, 2013

Swans of the Kremlin: Ballet and Power in Soviet Russia

|

| Galina Ulanova and friend watch a student perform

By Christina Ezrabi, Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2012

An academic text about the role of ballet in the early days of Soviet Russia. The Mariinsky (later Kirov) and the Bolshoi troupes where the only ballet companies with imperial status, and after initial suspicion, the Soviets tried to co-opt the glory of pre-revolutionary culture to their own ends. The Soviet regime worked to dispel Russian "backwardness" by promoting "kul'turnost," making bastions of high culture available to the common worker. They argued that Soviet citizens read more books than any other people on the planet and had access to superb ballets. This book helped me to understand the "Russianness" of Mariinsky and Bolshoi dancers today: the emphasis on character dances, the history of the drambalet, their enduring mastery of ballet cannon such as Swan Lake, and the role of the Vaganova Ballet Academy. |

Old Morality

|

| Henry Raeburn, Sir Walter Scott, 1822

By Sir Walter Scott, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2009

A story of 17th century war between Tories and Whigs in Scotland. A critical introduction, notes, and a glossary made this a much richer reading experience than my earlier attempt at reading Sir Walter Scott.

|

The Unreal Life of Sergey Nabokov

| Set design for the Ballets Russes

By Paul Russell, Berkeley, CA, Cleis Press, 2011

A wonderful novel about Nabokov's younger, gay brother set in Berlin, St. Petersburg, and Paris. The story offers a whirlwind tour of early modernism with Diaghilev, Cocteau, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas all making appearances. This book is great fun and captures the heady parade of early 20th century European culture.

|

Tuesday, October 8, 2013

Pride and Prejudice: An Annotated Edition

|

| Sir Thomas Lawrence, Margaret, Countess of Blessing, 1822

By Jane Austin, ed. by Patricia Meyer Spacks, Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press, 2010

Ah, what a glorious edition of Pride and Prejudice! This is a richly illustrated and lavishly annotated edition of a novel that is, by now, almost too famous for its own good. I am so familiar with the story of Elizabeth Bennet and Darcy through movies and the novel itself that I wasn't sure what I could gain from rereading Austin's tale. Spacks is a wonderful companion for the reader. The notes summarize scholarly debate without losing site of what may interest the general reader. It was a real pleasure to read P&P slowly and carefully with Spacks as my guide.

|

The Bride of Lammermoor

|

| Natalie Dessay in The Met's Lucia di Lammermoor

By Walter Scott, s.l., s.n., no date

Lucia di Lammermoor is my favorite opera, and I couldn't wait to read the novel behind the performances that I've loved so well. What's better than Lucia's Mad Scene? Big mistake. I bought a horrible edition from Amazon without an introduction, textual notes, or anything to aid the reader. The narrative is in standard English, but I don't read Scots! I could get the gist of what occurs in any given scene without being able to decipher the individual words, but geez. The narrative gallops along, and I tried to immerse myself in the Romeo and Juliet story of Lucia and Lord Ravenswood. I did a little online research to better understand the political dynamics of 17th century Scotland, the setting of the story, but without the necessary context, this novel was a slog.

|

Thursday, September 26, 2013

The Return of Jeeves

|

| Hugh Laurie and Stephen Fry as Bertie and Jeeves

By P.G. Wodehouse, New York, Avenel Books, 1983

Reading the novels of P.G. Wodehouse is a singular experience. I've been a fan since the 1980s, and its like entering an Anglophilic dreamscape. Jeeves is the perfect "Gentleman's Gentleman," and Bertie is the most charming dimwit in all of literature. I can't really tell the Bertie and Jeeves novels apart. The plots are so trivial and formulaic, yet the prose is undeniably enjoyable. I am so taken with PGW that I've even read his golf short stories. That's devotion!

|

Wednesday, September 25, 2013

This is How You Lose Her

|

| Mr. Diaz mugging for the camera in a wooly hat!

By Junot Diaz, New York, Riverhead Books, 2012

More finely crafted short stories by the very skilled Junot Diaz. He's complained in interviews that he is a very slow writer. Each story is like a finely crafted jewel. I wish he was from LA. I'd enjoy his perspective on West Coast life. The quintessential American is an immigrant, so his tales feel both utterly familiar and utterly alien.

|

The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

|

| Junot Diaz with his novel

By Junot Diaz, New York, Riverhead Books, 2007

Oscar is fat, smart, loves science fiction, and is part of a truly crazy Dominican family. There's a lot to love in Diaz's storytelling. He writes in a literate and funny version of Spanglish. I often don't understand the Spanish words he using in the novel. That's OK with me. I grew up in LA where I didn't understand 95% of the Spanish spoken around me. There are footnotes about DR history and political culture that are quite interesting. There's pain and suffering in the story, but its off-set by elements of magical realism and a warm, wry narrative voice. |

Friday, September 20, 2013

Drown

|

| The first immigrant to NYC was Juan Rodriguez, from the Dominican Republic. The Dutch Came Later! |

By Junot Diaz, New York, Riverhead Books, 1996

A collection of early stories by Diaz that focus on the immigrant experience of moving from DR to the East Coast. They are surprisingly gritty and disturbing.

The Blue Hour: A life of Jean Rhys

|

| Jean Rhys, ca. 1920

By Lilian Pizzichini, New York, WW Norton & Co., 2009

Jean Rhys was a difficult person who lived a hard life and possessed a rare literary talent. The strength of this biography is that Pizzichini wants to tell the tale of Rhys's life as she experienced it. Rather than labeling Rhys as having a "borderline personality disorder," Pizzichini creates an empathetic portrait of the author. Rhys wrote Wide Sargasso Sea while in her 70s and often consuming a bottle of whiskey per day. |

Sunday, September 15, 2013

Wide Sargasso Sea

|

| Brassai, Cathedral, ca. 1930

By Jean Rhys, New York, WW Norton & Co., 1985

After a break from writing for over twenty years, Rhys wrote Wide Sargasso Sea in the 1960s, and it reads like a delirious nightmare. The sensibility is the same--this is clearly a Jean Rhys work--and she reimagines Jane Eyre from the perspective of Grace Pool. Pow! It is like a brilliant hallucination. Her concern for those passed over as marginal, crazy, or foreign is fully evident here. This is post-colonial literature in the best tradition of "the empire strikes back." (Although, the heroine is a white Creole. This isn't The Beloved.) The novel bursts forth with the fully realized power of a distinctly alternative view point.

|

Good Morning, Midnight

|

| Brassai, Untitled, ca. 1930

By Jean Rhys, New York, WW Norton & Co., 1985

My favorite of Rhy's early novels. Sasha Jensen is her most articulate heroine. She is in her late 30s or early 40s and looks within herself to understand life's pain. Sasha is sloshed but doesn't indulge in self-pity. This novel is about how tenuous human connections are and the unrelenting grind of poverty. The strength of Rhy's work is that she focuses on the interior landscape of her heroines. The outside events in her novels are fairly uniform, so she turns her attention to the feelings and motivations of her characters. Her characters are Bohemian lounge-abouts, but sensitive and perceptive too.

Good Morning, Midnight! I'm coming home, Day got tired of me-- How could I of him? Sunshine was a sweet place, I'd like to stay-- But Morn didn't want me--now-- So good night, Day! Emily Dickinson |

After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie

|

| Brassai, Untitled, ca. 1930

By Jean Rhys, New York, WW Norton & Co., 1985

Julia Martin is in her mid-30s and living in Paris when Mr. Mackenzie dumps her. She leaves for her native London where she confronts her sister who has a lived a life of middle-class, though impoverished, conformity. Unable to earn a living--we also learn that she is divorced and her child has died--she asks former lovers for money. Disappointed, she returns to Paris and her life resumes its pattern of drink, hotel rooms, and hurt feelings. Julia is neither a successful member of Bohemia nor a bourgeoisie. She drifts along on the edge of both worlds. All of Rhys's heroines are betrayed, alone, and poor. |

Quartet

|

| Brassai, Untitled, ca. 1930

By Jean Rhys, New York, WW Norton & Co., 1985

We are in what is clearly Jean Rhys Land: a young woman in the 1930s drinks to excess, lives in a series of hotel rooms, asks for gifts of money from ex-lovers, and suffers a great deal. I don't mean to be flip. There's an undeniable freshness and honesty about Rhys work that is very winning. Marya Zelli marries a Polish thief, he is caught and thrown into jail. She becomes involved in a menage a trois with rich expatriates. Misery all around.

|

Voyage in the Dark

|

| Brassai, Untitled, ca. 1930

By Jean Rhys, New York, WW Norton & Co., 1985

Anna Morgan is from the West Indies and living in inter-war (or pre-WWI?) London. Her father is dead, the rest of her family apathetic, and working as a chorus girl. Her first affair ends in an abortion. Rhys's style reminds me of Vermeer: the prose is precise, closely observed, and concerned with the things of everyday life. Anna's passivity in the face of psychological disaster is noteworthy. She is vacant, empty, ghost-like as she moves through the world. Her only escape is alcohol when seemingly anything might happen. She drinks until bedtime and then pulls the covers over her head to dream of her childhood.

|

Tuesday, September 10, 2013

The Beloved

|

| Slave Irons: Collar

By Toni Morrison, New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1998

This novel is a searing read. I had a stomach ache while reading it, and my eyes frequently welled up with tears. Both the story's content (the personal and collective devastation to African Americans by the institution of slavery) and Morrison's style (a lyrical, fragmentary, and elliptical way of telling her story) are very effective. I especially like how deeply Morrison understands the work of trauma in shaping memory, forgetting, and identity. Trauma can be defined by painful memories that intrude in the course of everyday life. The past is co-present with the Now in a powerful way for trauma victims. It also engenders, paradoxically, the necessity of forgetting. This is the best novel I've ever read about American culture. |

Kristin Lavrandsdatter

|

| Borgund Stave Church

By Sigrid Undset, trans., Tiina Nunnally, London, Penguin Books, 2005

Undset's romantic prose was, initially, a relief after reading so much Anthony Powell. The novel follows the arch of one woman's life from childhood to her demise in the Black Death. The strength of the novel is the author's deep knowledge of everyday life in 14th century Norway. Her father was an anthropologist and she grew up surrounded by medieval artifacts. I remember learning in college that European culture was the result of three factors: the Nordic/ Germanic tribes, the learning of the ancient world housed in monasteries, and Christianity. These influences are clearly on display in Kristin Lavrandsdatter.

|

Saturday, August 24, 2013

Hearing Secret Harmonies

|

| Arnold Newman, Cecil Beaton, 1978

By Anthony Powell, Chicago, University of Chicao Press, 1995

Viola! Finis! The final novel in Dance. AP's world view revolves around two poles: the exercise of domination--a will-to-power--along with chance and coincidence. These are the two factors that move the plot forward in Hearing Secret Harmonies and throughout the 12 novel cycle. Jenkins is now a believably middle aged novelist living in the late 60s or early 70s when the story opens. His family hosts a caravan of hippies that include is niece, Fiona Cutts, and a creepy cult leader named Scorpio Murtlock. Widmerpool is a chancellor at a US university and a convert to the counter culture. Nick visits Matilda Donners and is shown the photographs of the Seven Deadly Sins tableaux taken decades ago. The Donners Memorial Prize, a literary award, is established, and Jenkins is a member of the jury panel. Russell Gwinnet is awarded the prize for his biography of X Trapnel. Fiona leaves Murtlock's cult and marries Gwinnet. Widmerpool is back in England and takes up with Scorpio or "Scorp" as he calls him. Widmerpool and Murtlock battle for control of the hippies, and Widmerpool suffers a humiliating defeat. With tragic absurdity, Widmerpool dies running naked with the cult in the early morning hours. The novel ends, as the series began: workmen are laboring in the street and this reminds AP of the stories, myths of the ancient world.

So, how is AP like Proust? Not very is my response. I found an old but wonderful book about AP entitled Criticism of Soceity in the Englsih Novel Bewteen the War by Hena Maes-Jelink that helped me think more clearly about this question. Maes-Jelink writes, "Feelings are set to one side and a real exploration of personal relationships are left off." This captures what I find so frustrating about Dance. Jenkins rarely ventures beyond the world of appearances. By contrast, Marcel is so extremely sensitive and possesses a rich emotional life. There isn't much psychological analysis in AP. Maes-Jelink continues, "Powell reconstructs the past chronologically without referring to the inner life of his characters; he relies almost exclusively on facts to describe relations between individuals and between individuals and society." |

Temporary Kings

|

| Cecil Beaton, Ian Fleming, 1962

By Anthony Powell, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1995

Things really heat up in this penultimate novel of Dance to the Music of Time. In the late 1950s, Jenkins attends a literary conference in Venice. He meets Russell Gwinnet, an off-putting young American academic, who hopes to write a biography of deceased X Trapnell. While looking at a fresco by Tiepolo in the Bragadin Palace, Gwinnet is introduced to Pamela, and he asks to interview her for his book. (The painting is a mythical subject in which a king hides a courtier behind a drape so the courtier can see his nude wife. Hint, hint: this will become symbolic later.) Pamela is attended by Louis Glober, an American director. Kenneth arrives, and the Widmerpools fight. There's gossip that Pamela slept with the French author Ferrand-Seneschal on the night of his death, and a waft of necrophilia hangs in the air. Back in England, Jenkins learns that Pamela is courting Gwinnet, and Widmerpool may have been arrested for spying. Moreland hosts a Mozart concert with Glover and Polly Duport, the actress daughter of Bob Duport and Jean, in attendance. The Widmerpools kick up a tussle, and Mrs. Erdleigh warns Pamela that she is on a dark path. Moreland becomes ill after the concert and dies. Pamela dies of a drug overdose while in bed with Gwinnet. Pamela's relationship with Ferrand-Seneschal introduces the idea that sexuality and death are dangerously combined in her life. The real kicker comes, however, when we learn that Widmerpool was watching Pamela and the Frenchman have sex from behind a curtain on the night that Ferrand-Seneschal died! Furthermore, Widmerpool is let off of spying charges only because he ratted out the communist Ferrand-Seneschal. There's betrayal all around. I understand the title of the novel to mean that Jenkins and his cohorts are at the height of their powers. They are successful economically, socially, and part of the culturally ascendant group, but nothing lasts for long in Post-war England. They are only temporary kings. At this late date, I have to admit that AP is starting to win me over. I've invested hours watching this high-class quadrille spin itself out. There's a formal, abstract beauty in the way he plots the story. The sweep of Dance is impressive. I love the complex relationships that form and dissolve across the 20th century throughout the novels. Pamela emerges as something more than a one-dimensional archetype here. My complaint with the previous novels this that AP repeatedly asserted that she was beautiful without showing the reader what qualities made her so compelling. AP seemed unable to name her mysteries: glossy hair and a trim figure can't make up for such a nasty personality. The reader knows from Books Do Furnish a Room that Pamela's sexuality is a surface thing. X fumed that she initiated sex frequently but was curiously "dead" and unresponsive in bed. I wonder if sexuality in Dance is notable for being about power? Sir Magnus Donners, after all, was a Peeping Tom who built secret compartments into Stourwater so he could spy on his lovers. |

Books Do Furnish a Room

|

| Cecil Beaton, Graham Vivian Sutherland, Somerset Maugham, 1949

By Anthony Powell, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1995

9 novels down and 3 to go until I finish Dance. Good grief! The plot is this: its 1945 and Jenkins returns to his university (Cambridge or Oxford, natch) after the Wars to research a book on Robert Burton, the 17th century author of The Anatomy of Melancholy. While visiting Sillery, Jenkins meets his new secretary, Ada Leintwardine. Quiggin starts a literary magazine called Fussion. This venture was to be sponsored by Erridge, but he suddenly dies. Erridge's funeral at Thrubworth brings together Quiggin, the Widmerpools, and Gypsy Jones (now Lady Craggs). At a launch party for the magazine, Jenkins encounters the dapper bohemian, X Trapnel. Pamela and Trapnel start an affair, and Pamela flees Kenneth. Pamela eventually abandons Trapnel and throws his book manuscript into a canal. The novel ends with Jenkins returning to his old prep school (the scene of the action in A Question of Upbringing). La Bas is in his 80s and working in the school library as a reference librarian. The Widmerpools are also visiting the school that day, and Kenneth leans against a stone wall in dejection. |

Friday, August 23, 2013

Coming into Fashion: A Century of Fashion Photography at Conde Nast

|

| Edward Steichen, Lee Miller, 1928

By Nathalie Herschdorfer, Munich: Prestel, 2013

I spent an enjoyable summer afternoon reading this book on my couch escaping from the oppressive heat. Its instructive to read a survey of the nude in contemporary art before an overview of 20th and 21st century fashion photography. One can clearly see how representations of the ideal body migrated from elite to popular culture. Herschdorfer offers a competent survey of photographic trends from 1911 to 2011, but I was struck by the fleeting, superficial impact these images had on me. Fashion photography is extremely pleasing and utterly forgettable. Fashion photography offers up an entire lifestyle, an alternative world where aesthetics and a commodified, consumerist notion of beauty reign supreme. These representations are ultimately unsatisfying because they never get anywhere--there's not a trajectory of a medium like in art history--and they eschew genuine ambiguity. Fashion photography is imprisoned by elegance. Glamour and sexiness are endlessly defined in these images, but at the cost of greater artistic meaning. As Herschdorfer notes, "If we study a century's worth of fashion photographs, what we notice is that the genre is forever reinventing itself from the same staring point." |

Wednesday, August 21, 2013

The Naked Nude

|

| John Currin, Bea Arthur Naked, 1991

By Frances Borzello, London: Thames & Hudson, 2013

The idealized nude is a staple of art history and it is my favorite type of genre painting. Kenneth Clark famously stated that being naked is the condition of being without clothes, but the nude is art with a capital "A." Clark wrote, "The vague image it projects into the mind is not of a huddled or defenseless body, but of a balanced, prosperous, and confident body: the body reformed." The nude, as Borzello so helpfully notes, "in art is a victory of fiction over fact." She asserts that the birth of modernism marks the end of the idealized nude. Contemporary artists turn away from the depicting the perfect body and focus on our conflicted ideas about what it means to have a body. We are obsessed with food, health, sexuality, weight, fashion, pornography--all topics that hinge on the problem of embodiment. For example, John Currin once said that he like to paint images that embarrass him. Indeed! Looking at Bea Arthur Naked causes me to squirm. I want to say, "Maude, please put your top on!" Bea Arthur looks perfectly composed and dignified, but she has Mom breasts. In addition, that 80s hair style really hits too close to home. |

Monday, August 19, 2013

The Price of Inequality: How Today's Divided Society Endangers Our Future

|

| Damien Hirst, richest artist in Western Euope and friend of oligarchs everywhere |

By Joseph Stiglitz, New York: WW Norton & Co., 2013

With crystal clear prose and a well-organized argument, Stiglitz offers a devastating critique of contemporary American society. He writes, "We have a political system that gives inordinate power to those at the top, and they have used that power not only to limit the extent of redistribution but also to shape the rules of the game in their favor and to extract from the public what can only be called large 'gifts.'" Stiglitz introduced me to the vitally important concept of rent seeking that he defines as obtaining income not as a reward for creating wealth but as the end product of jiggering the political and market environment to one's own advantage. To put the question baldly: one can become wealthy by creating income or one can take it away from others.

I now see rent seeking all around me: agricultural subsidies that go to million dollar corporations; mining companies that extract resources from national parks and pay less than what the commodity is worth; the opaque and unregulated health care industry governed by kick backs and the drive for 20% annual profits; low-wage workers paid with Chase debit cards that charge a fee every time these employees use the card or obtain a "cash advance." These rents move dollars from the bottom and the middle to the top. Stiglitz explores aspects of the political and social systems in America that are rigged in favor of the 1%. A powerful and depressing book.

Monday, August 12, 2013

Nijinsky: A Life of Genuis and Madness

|

| Vaslav Nijinsky in costume for the ballet Le Spectre de la Rose, ca. 1912

By Richard Buckle, New York: Pegasus Books, 2012

Buckle was a dance critic, curator, and scholar of the Ballets Russes. He was a pall bearer at Nijinsky's funeral and decided it was his mission to "collect every single surviving Diaghilev design in the world." This is a lively, fun book full of sharp insight. It reads like a Vanity Fair profile crossed with an academic text. Buckle does an excellent job in laying out the social milieu and cultural world of the Ballets Russes. There is no extant film of Nijinsky dancing, but Buckle works hard to convey the astonishing grace and daring innovation of Nijinsky's career. His decline into mental illness, he suffered from schizophrenia, is truly heart breaking. |

Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes, 1909-1929: When Art Danced with Music

|

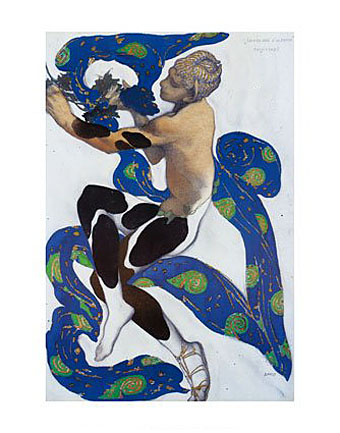

| Leon Bakst, Costume design for Vaslav Nijinsky as the Faun from The Afternoon of a Faun, 1912

Edited by Jane Pritchard, London and Washington, DC: V&A, NGA, 2013

This is the exhibition catalogue for the eponymous show at the NGA on the Ballets Russes. Sergei Diaghilev was a masterful impressero who created the Ballets Russes troupe specifically for European (and eventually North and South American) audiences. It was a touring company. Diaghilev combined classical ballet with European high modernism and venacular Russian folklores. The exhibition was arranged chronically which helped me learn about the different artistic phases of the Ballets Russes. Diaghilev created productions that fused together dance, music and design in pursuit of "total art," or gesamtkunstwerk.

|

Monday, June 17, 2013

The Military Philosophers

|

| Cecil Beaton, Daisy Fellows, 1941

By Anthony Powell, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1995

This is the final book of AP's "war trilogy" and the ninth book in Dance to the Music of Time. Its 1942, and Jenkins is working with Finn, assigned to the Poles in Allied Liaison, and Pennistone. Jenkins visits Polish HQ which is housed in the Ufford Hotel. His driver is Pamela Flitton, femme fatale and Stringham's niece. Pamela informs Jenkins that Stringham was captured when Singapore fell.

One night during 1944 while living in Chelsea, Jenkins meets Pamela and her lover Odo Stevens during a bombing attack. Mrs. Erdleigh makes prophecies about everyone's future while Odo and Pamela fight.

Jenkins makes a tour of Normandy and Belgium with a party of Allied military attaches. While in Brussels Jenkins meets Bob Duport who tells him that Peter Templer died in the Balkans. Stringham is assumed dead.

By the end of the war, Miss Weedon is engaged to Sunny Farbrother, and Widmerpool is due to marry Pamela. At a party, Pamela accuses Widmerpool of intentionally putting Templar in harm's way. There is a victory thanksgiving service at St. Paul's Cathedral, and Jenkins meets Jean (nee Templar) who is now married to Colonel Flores, a Latin American military attache. Jenkins is released from the military and gets a new suit of clothing.

Three novels left. I am uninspired by AP to the point of feeling outright resistance. I don't think its an accident that Kingsley Amis and Philip Larkin (gasp!) are fans. |

Thursday, June 13, 2013

The Solider's Art

|

| Cecil Beaton, John Moore-Brabazon, 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara, 1940

By Anthony Powell, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1995

So, here's the plot: during the middle years of the Second World War, Nick Jenkins is in the Army working alongside Capitain Biggs, General Liddament, and Widmerpool. Jenkins is recommend to a liaison posting with the Free French military and meets Lieutenant-Colonel Lysander Finn. Clearly functioning as a symbol wasted promise, Charles Stringham pops up in the story working as a Mess Waiter.

While on leave in London, Jenkins has drinks with Chips Lovell, estranged from Priscilla, and Hugh Moreland. Mrs. Maclintick, now living with Moreland, joins the men for dinner. Awkwardly, Priscilla and her lover Odo Stevens arrive in the restaurant. Later that night, bombs rain down on London and kill Chips, Priscilla, and Lady Molly.

Returning to HQ, Jenkins discovers Widmerpool has transferred Stringham to the mobile laundry. Widmerpool's political machinations run afoul of Sunny Farebrother, a cunning officer and friend of Peter Templer's father. Stringham is posted to the Far East, and Captain Biggs hangs himself.

I continue to read AP's Dance to the Music of Time because I'm committed to working my way through The List. Tedious. |

Tuesday, June 4, 2013

The Valley of Bones

|

| Cecil Beaton, Sir Adrian Carton de Wiart, 1944

By Anthony Powell, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1995

Oh my gosh, the seventh book in Anthony Powell's A Dance to the Music of Time is a snooze fest. Just when I felt like I was getting into the High Tory groove, The Valley of Bones comes along and bursts that little bubble. This novel is awful. My mind wandered to my new poodle (see the picture below), a weekend trip to Pittsburgh, and the politics of scheduling at the American Ballet Theatre. In short, I would rather think about anything than the thoughts and feeling of banker-soldiers in the first days of the Second World War.

Snowball! The perfect Poodle puppy and Anthony Powell antidote

Its late 1939 or early 1940 in England, and Nick Jenkins is in the army. We're introduced to his commanding officer, Captain Gwatkin and the booze-soaked Lieutenant Bithel. The battalion Jenkins is attached to moves around England. Yawn. Nick makes friends with David Pennistone ("Penis Stone"!!), Odo Stevens, and meets up again with Jimmy Brent. Brent discusses his affair with Jean Duport, and, maybe its through osmosis of British reserve, a small part of me died at these revelations. How could Jean be so foolish? I imagined Jean was in thrall to her own sexuality, and her relationship with Brent was about self-knowledge, but, really, eh, Brent is so small. What was Jean thinking? I am worried about her and wonder what she's doing in South America.

Meanwhile, Odo Stevens drives Nick to Frederica Budd's house when Nick is granted leave. There, Nick meets his pregnant wife, Isobel, and his Tolland in-laws Robert and Priscilla. Odo and Priscilla, married to Chips Lovell, flirt. The scenes at Frederica's house had the most power. I was once again engaged with the characters I met in the first six novels. Why should I care about Nick's life as a solider? Will these characters endure throughout the other novels? Unlike other commentators, I am unmoved by the "humor" that contrast the officers--inevitably former bankers--and working-class soldiers.

AP shows us that this is a time of "massive upheaval" since great houses are repurposed as hospitals for the war effort, but men still brought servants to war. A batman was assigned to a commissioned officer as a personal servant. I am stunned that officers took their servants to war with them. Indeed, Bracey, who we met in The Kindly Ones as one of the servants Jenkins knew when a child, is revealed to be Jenkins's father's batman in WWI. Oh, how very organic. A man serves you in war and then follows you back to your estate in peace time as a servant. The bond between master and servant is strong indeed! Of course, I think this is gross. (Looking ahead to The List, I was reminded of Edward St. Aubyn's Patrick Melrose novels. Melrose's father cut his teeth in the sadistic corners of Imperial England)

In the last scene of the novel, Nick reports to HQ and meets Widmerpool. At this point, I'm rooting for the fat, ambitious, and bossy Widmerpool. Nick is a bland boy. |

Friday, May 31, 2013

The Kindly Ones

|

| Cecil Beaton, Chateau Cande, France, 1936

By Anthony Powell, Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1995

This novel marks the half-way point through APs cycle A Dance to the Music of Time. The Kindly Ones is a title that has several meanings. WWII is just about to be declared, and the title symbolizes the gathering winds of war. Ancient Greeks called to the Furies "the kindly ones" in an attempt to placate them. We finally learn some interesting personal information about Jenkins. AP takes us to his childhood home and introduces us, surprisingly, to the charming servants who worked for his parents. Albert, a pessimistic artist-cook, refers to suffragists as "Furies," and Billson, a housemaid, sees ghosts. Jenkins's world is haunted.

Jenkins visits the Morelands at their home near Sir Magnus Donners castle Stourwater (which can be read as "sour water" to a "t"), and everyone gathers chez Donners for a party. Peter Templer, now a coarse stock broker with a rich man's swagger, is present with his fragile blond second wife, Betty. Playing dress up, they act out The Seven Deadly Sins as tableaux while Sir Donners takes their photographs. This is vividly drawn. Kenneth Widmerpool makes a surprise appearance at the end of the night purportedly to discuss business!

Uncle Giles dies in a provincial hotel, the Bellevue run by Jenkin's childhood servant Albert, and Jenkins travels there to see to the body. While at the Bellevue, he meets Bob Duport, Jean's ex-husband. Jenkins tries to get into the military, and while at Lady Molly's runs into Hugh Moreland. He is homeless and lost. Mathilda threw him over for Sir Donners. Okidoki, the next three novels are AP's most acclaimed in the opus--they constitute a trilogy about WWII. I'm rushing through the cycle. Unlike most readers, I am not in love with AP's prose. His vocabulary is arcane and arch, but I love the way he structures the plots. The characters weave in and out of the story so effortlessly, and I've often pulled in my breath with the unexpected sightings of Widmerpool. AP's sensibility and cultural references, as discussed in the last review, are too alien for me to feel much love. |

Thursday, May 30, 2013

Casanova's Chinese Restaurant

|

| Cecil Beaton, Wallis, Duchess of Windsor; Prince Edward, Duke of Windsor (King Edward VIII), 1937

By Anthony Powell, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1995

This book represents the fifth installment in AP's twelve novel opus, Dance to the Music of Time. The first part of the book rounds back to before Mr. Deacon's death, but the bulk of the plot concerns the narrator Nick Jenkins and his comrades Hugh Moreland and Maclintick. We learn little about Isobel Tolland and the state of Nick's marriage to her, but matrimony is a key topic here. Hugh Moreland, Nick's friend from university who is a music composer, struggles in his marriage to the jolie laide actress Matilda. The real fireworks in terms of interpersonal conflict, however, is between Maclintick, a music critic, and his spouse Audrey. Maclintick and Audrey sing arias of contempt and disdain. Their fights truly made me squirm in discomfort.

Erridge returns from an unsuccessful trip to Spain where he attempted to aid the anti-Franco forces in the Spanish Civil War. Widmerpool makes a brief appearance and frets over Edward VIII's abdication. Mrs. Fox gives a party to celebrate the performance of Moreland's symphony, and Stringham makes a sad, drunken appearance. Audrey leaves Maclintick, and in despair, Maclintick commits suicide.

Kaggsy's Bookish Ramblings has a supurb account of Casanova's Chinese Restaurant, no surprise there, and I uncovered Christopher Hitchens's jewel of a book review about Powell. Hitchens is very clear regarding Powell's attitude about class. Hitchens draws comparisons between AP and George Orwell and argues that Powell's elitism resides in breezy characterizations of those who stand apart from the beau monde and well-heeled bohemians. He is worth quoting at length:

But, what exactly is the social reference of "a thoroughly ill-conditioned errand-boy"? Hitchens identifies the "braying tones and judgments" contained in this description, but I don't understand what Hitchen is pointing to in "the implication of the word 'conditioned.'"

|

Sunday, May 26, 2013

At Lady Molly's

|

| Cecil Beaton, Merle Oberon, 1934

By Anthony Powell, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1990

OK, I've made it through the fourth of Powell's twelve novels in the cycle, Dance to the Music of Time. Jenkin's affair with Jean is over and he meets the woman who will be his wife, Isobel Tolland. Lady Molly's house is the novel's central location for conversation, and many of the characters from earlier books make an appearance there. Widmerpool is engaged to Mildred, a ferocious older woman, who really seems as if she could eat him alive. Quiggin, ex-secretary to St. John Clarke and an accomplished literary critic, invites Jenkins to a weekend at his cottage. Quiggin is now living with Mona until she dumps him for the head of the Tolland family, Lord Erridge Warminster. Mona--who I image looking like Merle Oberon so couldn't believe my luck in spotting the above Cecil Beaton portrait--and Erridge run off to China. This relationship seems to symbolize the meeting of bohemia, Mona is a raw-edged model and actress, and landed aristocrats, Erridge is a Lefty who has more money than he knows how to spend but is, nevertheless, quite cheap. As I speculated in an earlier review, AP's world is that depicted by Cecil Beaton in many ways: both are concerned with members of the upper-crust and what we would now call "the creative class." It goes without saying that I don't share AP's social references. The class contrast and power dynamic between Quiggin and Erridge is very well done. Quiggin is brittle, smart, and sees right through Erridge, his patron. Erridge's parsimonious concern for "the masses" felt like a depiction of Robespierre. I keep reading for the unannounced Tory convictions of AP. I think his political conservatism lives at the level of social/ political touch points in the text itself. Who AP imagines he is addressing as the reader of the novels. He's really very off-handed about privilege. Widmerpool's marriage is eventually called off. Widermerpool is such a vile man but he's the source of much of Powell's irony here. (His family makes artificial manure, his marriage fails to come off because he is too sexually inexperienced for Mildred, and the novel ends with Widermerpool smugly offering advice on marriage to Jenkins.) I thought this was the funniest and most charming book in the series by far. There are references in the text to Freud, the Ballets Russes, the rise of Fascism and other concerns of high society in the1930s. The books' narrative structure consists of telescoped events that are carefully explored rather than a broad synthetic tale. Just as part of the delight in reading AP is his examination of small, mundane coincidences, there are a lot of gaping holes in the story too. Isobel Tolland, for example, dropped out of the story once she was introduced, and I wonder what happened to Stringham. He was so drunk and miserable when we last saw him! Kaggsy's Bookish Ramblings, as usual, has the best review of At Lady Molly's |

Thursday, May 23, 2013

Impressionism, Fashion, & Modernity

Saturday, May 18, 2013

The Acceptance World

|

| Bert Longworth, Cecil Beaton, 1930s

By Anthony Powell, Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995

This is the third novel in Powell's cycle A Dance to the Music of Time. My review of the first novel is here and the second novel is here. Jenkins has an affiar with Jean Templer (now Duport), Widmerpool is making a killing in the financial markets, and Stringham is divorced and drinking too much. I feel like I am finally getting the gist of Powell's project. Jenkins is still a bit of a mystery, but the prose seems more concrete and less elusive. I'll never love the AP as much as the blogger at Kaggsy's Bookish Ramblings, but the novel's world is starting to cohere. The female protagonists came alive in this installment. Jean clearly has a life that extends beyond her interactions with Jenkins, and Mona, Peter Templer's unhappy spouse, is a fully-realized character. The title refers to a financial maneuver Widmerpool performs, but "The Acceptance World" also stands as a metaphor for life "as one approaches thirty." Jenkins and his friends from school are grappling with adult responsibilities and making compromises in the course of their lives. The action occurs in the 1930s: there are workers' demonstrations, and the novelist St. John Clark becomes a communist. Social and political change is clearly underway, but I was struck at the divorce of the rich from the poor. The novel ends with Jenkins, Templer, Stringham, and Widmerpool attending an Old Boy dinner at the Ritz to honor their ex-housemaster Le Bas. Like Henry Green's Party Going, the elite are isolated (and protected) from the masses while enjoying a fun night out. The old order may be passing away but privilege endures. |

Friday, May 3, 2013

A Buyer's Market

|

| Cecil Beaton, Margaret Emma Alice Asquith, Countess of Oxford and Asquith, 1927 |

Set during the interwar years, this is the second novel in Powell's cycle about a group of aristocratic and haute bourgeois Londoners. I'm looking at photographs of Cecil Beaton to imagine Powell's world. I wonder if Beaton's sitters aren't too artistic, however. I'm not sure Powell's mise-en-scene is this glamorous. Once again, I feel like I'm trying to discern the social life and customs of Martians.

The story opens with a night of debutante balls in London, and the novel's action centers around the families of Nicolas Jenkins, Peter Templer, Charles Stringham, and Kenneth Widmerpool. At the night's first party, Barbara Goring, a lovely but willful young woman, pours sugar over the head of the piggish Widmerpool. Widmerpool and Jenkins later meet Mr. Deacon, a painter of dull history pictures, and Gypsy Jones, a fetching anti-war activist. Widmerpool and Gypsy have been having an affair, and Widmerpool pays for her to have an abortion. Within the context of the novel, I was genuinely astonished. (Did I dream this? It is so out of step with the rest of the tale!)

Sir Magnus Donners, Widmerpool's employer, hosts lunches at his estate, Stourwater. During one of these parties, Jenkins becomes reacquainted Jean Templer, Peter's slender and remote sister. She's married to Bob Duport, Jenkins's friend from university. Jenkins yearns for Jean but admits that the "sluttish" Gypsy is quite attractive. Its hard to tell, but I think Jenkins has an affair with Jean. In any event, love is in the air: Charles Stringham marries Peggy Stepnev, Barbara becomes engaged to a solider, and Jenkins sleeps with Gypsy. The renewal promised by romantic love is contrasted with the inexorable march toward the grave. Mr. Deacon dies after his birthday party.

I don't understand the title. What is the buyer's market being referred to? Is the commodity human connection and love? Social capital is very important in Powell. I wonder if the competitive social scene where money and birth are two pillars of influence are the commodities? As an aside, I so enjoyed reading Kaggsy's Bookish Ramblings on Powell.

Tuesday, April 23, 2013

A Question of Upbringing

|

| Nicolas Poussin, A Dance to the Music of Time, 1634-1636

By Anthony Powell, Chicago: U. of Chicago Press, 1995

The first novel in Powell's twelve-volume cycle entitled A Dance to the Music of Time, after a history painting by Poussin. Powell's work represents a sort of High Tory take on the 20th century, and he is frequently cited as a British Proust. I read The Guardian's "Digested Read" by John Crace before actually plunging into the text. This means I could only read Powell's work as parody. Describing the opening of the novel, Crace is beyond brilliant:

For some reason, a glimpse of the lower orders warming themselves at a brazier in the street made me think of the ancient world. These classical projections in turn suggested a Poussin scene, where Time gives shape to the steps of the dance that had hitherto felt unfamiliar. So where better to start my meandering epic than at the school - there is only one so I need not be so vulgar as to name it - where these classical allusions first became choate.Oh, yes, this is the right tone to take with Powell. The narrator sees men at work in the street, this reminds him of the ancient world, his thoughts shift to Poussin's painting, and all this end with a mediatation on his life at Eton. The narrator, Nicholas Jenkins, is a snob who likes housemates Charles Stringham and Peter Templer, they are rich and elegant, but not Kenneth Widmerpool, he is a grunting little striver. Eventually Jenkins lands at university (either Oxford or Cambridge) where his social life centers around Professor Sillery's tea parties. This is England in the 1920s. I enjoyed the pacing of the novel. Events proceed at an even pace that isn't languid but denotes a modern, pre-digital era when mothers drove up from London to have lunch in their son's rooms. |

Where Snowflakes Dance and Swear: Inside the Land of Ballet

| Carla Korbes, principal dancer at Pacific Northwest Ballet, in Swan Lake

By Stephen Manes, New York: Cadwallader & Stern, 2011

A fun, informal look at the daily life inside an important regional ballet company, the Pacific Northwest Ballet (PNB) in Seattle. I learned a lot from this book about how ballets are transmitted from a contemporary choreographer to different ballet troupes. A stager is dispatched to a company who assumes primary responsibility for a ballet: the stager casts the dance from company members, teaches the dance to the dancers (often with the help of digital recordings), signs off on the costumes, stage lighting, scenery, and even the tempo of the music. Much of the work I assumed was performed by a company's Artistic Director is actually the job of the stager. Christopher Wheeldon, Twala Tharp (she's difficult!), and Susan Stroman make cameo appearances in the text.

At 897 pages this book certainly could have used an editor, but I'm glad I plowed through it. I often felt that Manes was recording episodes he witnessed while observing the PNB without any thought to their significance. I enjoyed his portraits of the ballet dancers. I felt relieved when Noelani Pantastico finally decided to move to The Monte-Carlo Ballet. Carla Korbes, while unmistakeably gorgeous, is too much of an obvious favorite to win my heart. |

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.JPG)